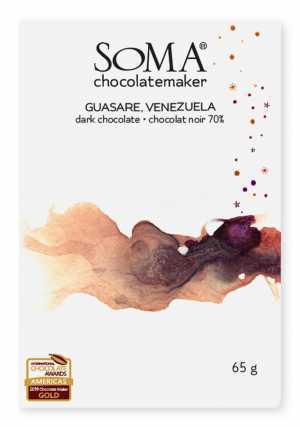

Artisan chocolate-makers David Castellan and Cynthia Leung have been at the forefront of Canada's bean-to-bar movement since 2003. Their original factory shop in Toronto's Distillery District is a brick-and-beam beauty housed in a former whisky distillery. Its industrial, old-world charm includes harvest tables laden with chocolate-tumbled nuts and cookies, and shelves stocked with single-estate origin bars. On full display, the Willy Wonka magic of chocolate-making beckons children to squish their faces up against the glass-lined walls. Since those early days, their SOMA Chocolatemaker concept has grown to be a local favourite, and one of the most awarded and recognized chocolatiers on an international level.

"We don't really think of ourselves as leaders, but part of a movement of first wave, small-batch makers that was happening globally," Leung says. "With that growth there are now more small-scale partners making machines; small farms; and educators, agronomists and scientists studying cacao. We all fit together as small parts of a larger movement."

David Castellan and Cynthia Leung of Toronto’s SOMA Chocolatemaker have been at the forefront of Canada’s bean-to-bar movement

Despite SOMA's success, the road to fine bean-to-bar — or craft — chocolate has been a long time coming in Canada. Think of where coffee was about 10 years ago in terms of accessibility and consumer knowledge, and you start to get a picture of where we are today with bean-to-bar chocolate. That is, chocolate made directly from cacao grown by farmers, who ferment their own beans — much like coffee makers — to bring out different flavours, before drying and shipping to craft chocolate makers.

How to taste bean-to-bar chocolate

To get the most out of your craft bar, expert Mary Luz Mejia suggests you break off a piece of chocolate and breathe in its aroma. Close your eyes. Do you get notes of coffee, nuts or maybe raisins? Now put it on your tongue and let it melt by pressing it against the roof of your mouth. Slowly. No chewing! You might start off with a fudge brownie flavour that morphs into bright, sweet-tart raspberries and mellows out to a full-bodied red wine. Breathe deeply and enjoy the moment.

As a Level II International Institute of Chocolate and Cacao Tasting Certified Chocolate Taster, I can blind taste test melted chocolate, assess tasting notes and determine where a bar comes from — think of me as a chocolate sommelier. But in the beginning, I only knew I liked dark chocolate, not too sweet and not too bitter. What I learned along the way changed my mind and my tastebuds.

When the Canadian leg of the International Chocolate Awards started in 2012, master juror, chocolate expert and competition co-founder Martin Christy described our chocolate scene as having some “good, traditional type chocolatiers and a very small number of bean-to-bar makers.” Bean-to-bar or micro-batch chocolate-making kicked off in the early 2000s in the United States and spread slowly to Canada. Christy says it took time for Canadian makers to source good cacao and perfect bean roasting, but over time they surpassed many makers in the U.S., as reflected by the many prizes they continue to win.

Qantu chocolate is made with heirloom cacao, grown on micro-lots in Peru

Now, in my chocolate-tasting classes, I teach participants about the kinds of cacao that go into commercial, commodity-grade chocolate (it’s traded on the NYC stock exchange), which includes candy bars and some of the chocolate sold in shops across Canada. When buying a candy bar, you’re likely buying mouldy, poorly fermented cacao that is susceptible to infestation by the cacao moth, which must be highly roasted for hygienic reasons. To make burnt cacao palatable, it’s flavoured with sugar and vanilla extract, which is why candy bars are, by law, called candy and not chocolate: The number one ingredient is sugar, not cacao.

In most chocolate shops, chocolatiers use couverture — prepared blocks of chocolate that are melted to make bonbons or bars. The marketing behind some couvertures is convincing, but strip that away and you’re left with a product that is, in many cases, not much better than commercial candy bars.

Colombian cacao is some of the world's finest. These Colombian cacao pods each hold dozens of beans

“This is just down to bad practice, cheap labour and varieties chosen for productivity over flavour. This applies just as much to famous chef couverture as it does to candy bars,” Christy says. “Just using the word Belgian does not make something good. Consumers want to know where their food is coming from and what the ethics and traceability of the ingredients are. Most chocolate experts agree the best bars are made with cacao from a single source, using a direct relationship with a single farmer, processor or co-operative.”

Just using the word Belgian does not make something good

In an industry worth $103 billion, you can see how tempting it is for multinational companies to diffuse the optics. One way to refocus the story is to turn attention to the sourcing of good cacao beans that are harvested by farmers (not children, as is often the case with commodity chocolate). This is paramount to creating good chocolate. Bean-to-bar makers tend to favour a Direct Trade approach, where a fair price is negotiated, and relationships are cemented between maker and farmer. But if you think that is the same as Fairtrade, you’d be mistaken.

Cacao drying

Direct Trade is a certification process with the prime goal of attaining a higher price for the farmer. As for Fairtrade, Christy says what started out as an idea with good intentions is now “not much more than a commercial label used to market chocolate and other products to consumers who are being hoodwinked.” He points to large, multinational chocolate producers who drop the Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance labels on products for their own, internally policed certification programs.

“Unfortunately, these programs don't really help farmers,” Christy says. “Usually, they are not targeting farmers in the countries where it would really make a difference. Instead, most Fairtrade cacao is grown in Latin American countries, where the standard of living might not be great, but it's higher than that of West Africa. Joining these schemes is expensive, everyone has to get paid along the chain, and you have to question who is benefiting.”

Qantu's bean-to-bar chocolate lineup

Peruvian-born bean-to-bar maker Elfi Maldonado, of Montreal’s award-winning Qantu Cacao et Chocolat, has spoken to farmers who say the few extra cents they get doesn’t cover the price of certification. “The minimum price for Fairtrade cacao is the stock market price. That price is absurd because, on average, it’s been roughly the same price for the last 50 years or so. And they don’t consider the quality of the beans,” she adds. To put this in context, a West African commodity cacao farmer might earn less than a dollar per day.

On Montreal’s east end, Maldonado and her husband Maxime Simard — who met while travelling in Cusco, Peru — have been making critically lauded chocolate since 2016. Inside Qantu’s white-walled and minimally decorated space, wooden easels showcase their award-winning and beautifully illustrated bars. The couple return to Peru in search of heirloom cacao grown on micro-lots, from the country’s Andean highlands to its tropical jungles, and buy directly from co-operatives, cutting out private companies or brokers. “We buy from people that work in the field, then we organize transport and pay for that separately,” says Maldonado.

Maxime Simard and Elfi Moldonado, the couple behind Montreal’s award winning Qantu Cacao et Chocolat, travel to Peru to source heirloom cacao beans, from the Amazon rainforest to the Andean highlands

Luckily, for fans of morally responsible chocolate, there are now hundreds of bean-to-bar makers in North America, and that number is growing globally. In just about any big city around the world, chances are good that you’ll find a craft chocolate maker.

Toronto’s SOMA Chocolatemaker deals directly with farmers or a company of the farm’s choice and their brokers. “We have trusted relationships with the people we partner with, that we have developed over many years,” Leung says. “They operate in ways that fit the model of good, clean, fair.” If Direct Trade isn’t possible, they often send large numbers of beans to one place and have a third party deal with logistics, she adds.

Montreal’s award-winning Qantu Cacao et Chocolat

There’s a lot that goes into sourcing good beans, including dealing with the geopolitical peculiarities of certain governments. At SOMA, Leung says, they work directly with farms in Jamaica, Ecuador, Madagascar, Fiji and Peru. To her, it’s important to develop relationships with farmers, many of whom have become good friends.

Colombian-born Cesar Aguilar, owner of Toronto's newer, online-only Cacaitos, works with a co-op of small farmers around his native country — and even grows some of his own cacao. Like the others, he deals directly with farmers, even going so far as to participate in post-harvest processes — quality control, sorting, packaging and preparing paperwork for exportation. His goal is to create a vertical integration business model, from farm to final product, in an attempt to cut out all “non-functional middlemen in the business chain.”

Cesar Aguilar recently opened Cacaitos, an online chocolate store that uses a co-op of small farmers from Colombia, where he was born

Why jump through so many hoops? As Christy says, “Good chocolate is all about the cacao, respecting and transforming the flavour of the cacao into good chocolate.” He argues that just as chefs choose the best possible ingredients for a dish, chocolate makers need the best-tasting cacao to make great chocolate. “This means actually tasting the cacao in its dried state and looking for flavour complexity and depth and a decent taste. It needs to be something you won't spit out,” he explains.

Canadian gems include Ontario saffron and Maple syrup

Canadian chocolate makers often highlight local ingredients, or “gems” as Maldonado calls them, to distinguish the chocolate made here. From Ontario-grown saffron and maple syrup to spirits, you’ll find these in craft bars with ‘inclusions,’ as they’re known in the industry. Leung believes it’s our multicultural country that makes Canadian chocolate so unique. “Food is the great connector of people and as Canadians, we are exposed to many different cuisines and ingredients that are readily available.”

Christy, who judges the Canadian leg of the International Chocolate Awards every year, says that while U.S. makers prefer deeper, woody notes, Canadians are more receptive to whisky and toffee notes. He cites Almonte, Ontario's Hummingbird Chocolate, which uses cacao from the Dominican Republic or Haiti, as an example of these caramel flavours. Qantu, Christy says, opts for Peruvian cacao, where the beans speak for themselves with a beautiful floral and fruity profile.

“I think the French influence allows Canadian makers to be more expressive, and we can see that in another Quebec chocolate maker Palette de Bine, who makes one of the best bars you can get using maple sugar. These are just a few of the good makers and it's scratching the surface really, there's a lot to explore,” he adds.

In fact, there’s a world of flavour to explore from cacao beans grown in Angola to Venezuela — and it’s all being made right here at home by craftspeople who care.